Is there life on Mars?

We'll go a roving

A series of missions currently underway will see NASA land a minirobot on Mars.

One of the aims is to determine whether or not life exists there.

The US' National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is working on a series of missions which could pave the way for a human landing on Mars, or even the establishment of a human settlement there, and which could also answer the tantalising question of whether there is, or once was, life on Mars.

If all goes well, we could have some startling news as early as the middle of next year. The missions are being managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of the California Institute of Technology, of Pasadena, California.

In spite of the loss of its previous Mars mission, (contact with the Mars Observer spacecraft was lost when it was about to enter into Mars' orbit in August 1993), and despite severe budget cuts, NASA has been vigorously developing a series of Mars exploration missions, involving orbiters, landers and rovers.

Under the Mars Surveyor Program, there will be about two launches to Mars every 26 months, when Earth and Mars are suitably aligned, from this year to 2005. NASA is also conducting the Discovery Program - a new generation of planetary exploration missions.

The first mission of the Mars Surveyor Program will involve the spacecraft Mars Global Surveyor, with a total mass of just over one tonne, to be launched in November this year aboard a McDonnell Douglas Delta 2 rocket, reaching Mars after about 10 months, in September 1997.

The mission's scientific goals are to increase our understanding of Mars' geology and climate. The mission will, for the first time, provide comprehensive data covering the whole of the martian surface, including the first complete map of the planet.

Sophisticated remote sensing instrumentation on board the orbiting spacecraft will gather data on the composition, distribution and properties of surface minerals, rocks and ices; the planet's topography and gravitational field; and its magnetic field. It will monitor global weather and the thermal structure of the atmosphere, and will monitor surface features, the polar caps, and the polar energy balance.

The mission also aims to provide several years of in-orbit communications relay capability for Mars landers and atmospheric vehicles for any nation interested in participating in international Mars exploration, and to support planning for future missions with measurements that could help select a landing site.

In spite of the loss of its previous Mars mission, (contact with the Mars Observer spacecraft was lost when it was about to enter into Mars' orbit in August 1993), and despite severe budget cuts, NASA has been vigorously developing a series of Mars exploration missions, involving orbiters, landers and rovers.

Under the Mars Surveyor Program, there will be about two launches to Mars every 26 months, when Earth and Mars are suitably aligned, from this year to 2005. NASA is also conducting the Discovery Program - a new generation of planetary exploration missions.

The first mission of the Mars Surveyor Program will involve the spacecraft Mars Global Surveyor, with a total mass of just over one tonne, to be launched in November this year aboard a McDonnell Douglas Delta 2 rocket, reaching Mars after about 10 months, in September 1997.

The mission's scientific goals are to increase our understanding of Mars' geology and climate. The mission will, for the first time, provide comprehensive data covering the whole of the martian surface, including the first complete map of the planet.

Sophisticated remote sensing instrumentation on board the orbiting spacecraft will gather data on the composition, distribution and properties of surface minerals, rocks and ices; the planet's topography and gravitational field; and its magnetic field. It will monitor global weather and the thermal structure of the atmosphere, and will monitor surface features, the polar caps, and the polar energy balance.

The mission also aims to provide several years of in-orbit communications relay capability for Mars landers and atmospheric vehicles for any nation interested in participating in international Mars exploration, and to support planning for future missions with measurements that could help select a landing site.

The Global Surveyor and its Payload Assist Module-D (PAM-D) upper stage will be carried into a temporary orbit around Earth by the Delta rocket. After the Delta separates from the spacecraft and falls away, the PAM-D will fire from a temporary orbit, freeing the spacecraft from Earth's gravity and placing it on a course for Mars. The spacecraft will then separate from the PAM-D and deploy its arrays to provide electricity to operate the craft and its scientific instruments.

Within 30 minutes of the Delta separating from the spacecraft, the Deep Space Network tracking station in Australia will acquire the craft's radio signal, checking and confirming its trajectory.

On arrival at Mars, the spacecraft will slow itself down by firing its main rocket engine and allow itself to be captured by Mars' gravity. It will first enter an elliptical orbit around the planet. Over the next four months, thruster burns and aerobraking maneuvers will change the orbit to a mapping, nearly circular polar orbit.

The mapping orbit has been carefully selected. It is about 370km above the surface, which is about as low as the spacecraft can get to obtain a close view. Lower than that and there is a danger the Martian atmosphere could drag the craft down.

The near polar orbit allows the spacecraft to progressively observe the whole of Mars' surface as the planet rotates below.

The orbit is also sun-synchronous, ie the spacecraft will pass over a given part of Mars at the same time of the Martian day. This is essential for atmospheric and surface measurements because it allows separating the effects of local daily variations from longer term seasonal and annual trends. The instruments aboard the spacecraft will gather data from April 1998 to April 2000.

The spacecraft, which is being built by Lockheed Martin Astronautics, has a rectangular body called the bus, made of light-weight composite materials. The bus houses computers, the radio system, solid state recorders, fuel tanks, and other equipment. Attached outside the bus are several rocket thrusters which will be fired to adjust the spacecraft's path during its cruise to Mars and to adjust its orbit around the planet.

The craft will orbit Mars so that one side of the bus will always face the Martian surface.

An X-band radio system and high-gain antenna will communicate with NASA's Deep Space Network tracking stations to provide a two-way link with the spacecraft. The spacecraft's communications system will also include a Ka-band link experiment that will demonstrate the next generation of deep space communications capabilities.

The data from the all the instruments onboard the craft will enable scientists to create, for the first time, a complete portrait of Mars. The seven instruments are the thermal emission spectrometer, laser altimeter, magnetometer, electron reflectometer, radio relay system, radio science investigation, and camera.

The thermal emission spectrometer will analyse the infrared radiation from the planet's surface. This will help identify the minerals that make up the planet's surface and will help determine several properties of the rocks and soils on its surface.

The laser altimeter will sample topography profile 10 times per second with a vertical precision of 2m. Laser footprint is 160m in diameter.

The magnetometer and electron reflectometer will establish whether Mars has a magnetic field and if it does, will establish the field's characteristics.

The radio science investigation will map variations in Mars' gravitational field by noting where the spacecraft speeds up or slows down in its orbit. It will also help map the vertical structure of the Martian atmosphere. Each time the spacecraft goes behind the planet or emerges from behind it, the radio beams will have to pass through the Martian atmosphere on their way to Earth. From the way the waves are distorted by the Martian atmosphere, the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere can be determined. The radio relay system will relay data from future Mars missions and from future Surveyor landers.

The camera will provide a daily wide-angle image of the entire planet and narrow-angle images of objects down to 1.5m in diameter. It will provide views similar to those obtained by terrestrial weather satellites. Some of the pictures will be sharp enough to help selecting landing sites for future missions.

The Global Surveyor and its Payload Assist Module-D (PAM-D) upper stage will be carried into a temporary orbit around Earth by the Delta rocket. After the Delta separates from the spacecraft and falls away, the PAM-D will fire from a temporary orbit, freeing the spacecraft from Earth's gravity and placing it on a course for Mars. The spacecraft will then separate from the PAM-D and deploy its arrays to provide electricity to operate the craft and its scientific instruments.

Within 30 minutes of the Delta separating from the spacecraft, the Deep Space Network tracking station in Australia will acquire the craft's radio signal, checking and confirming its trajectory.

On arrival at Mars, the spacecraft will slow itself down by firing its main rocket engine and allow itself to be captured by Mars' gravity. It will first enter an elliptical orbit around the planet. Over the next four months, thruster burns and aerobraking maneuvers will change the orbit to a mapping, nearly circular polar orbit.

The mapping orbit has been carefully selected. It is about 370km above the surface, which is about as low as the spacecraft can get to obtain a close view. Lower than that and there is a danger the Martian atmosphere could drag the craft down.

The near polar orbit allows the spacecraft to progressively observe the whole of Mars' surface as the planet rotates below.

The orbit is also sun-synchronous, ie the spacecraft will pass over a given part of Mars at the same time of the Martian day. This is essential for atmospheric and surface measurements because it allows separating the effects of local daily variations from longer term seasonal and annual trends. The instruments aboard the spacecraft will gather data from April 1998 to April 2000.

The spacecraft, which is being built by Lockheed Martin Astronautics, has a rectangular body called the bus, made of light-weight composite materials. The bus houses computers, the radio system, solid state recorders, fuel tanks, and other equipment. Attached outside the bus are several rocket thrusters which will be fired to adjust the spacecraft's path during its cruise to Mars and to adjust its orbit around the planet.

The craft will orbit Mars so that one side of the bus will always face the Martian surface.

An X-band radio system and high-gain antenna will communicate with NASA's Deep Space Network tracking stations to provide a two-way link with the spacecraft. The spacecraft's communications system will also include a Ka-band link experiment that will demonstrate the next generation of deep space communications capabilities.

The data from the all the instruments onboard the craft will enable scientists to create, for the first time, a complete portrait of Mars. The seven instruments are the thermal emission spectrometer, laser altimeter, magnetometer, electron reflectometer, radio relay system, radio science investigation, and camera.

The thermal emission spectrometer will analyse the infrared radiation from the planet's surface. This will help identify the minerals that make up the planet's surface and will help determine several properties of the rocks and soils on its surface.

The laser altimeter will sample topography profile 10 times per second with a vertical precision of 2m. Laser footprint is 160m in diameter.

The magnetometer and electron reflectometer will establish whether Mars has a magnetic field and if it does, will establish the field's characteristics.

The radio science investigation will map variations in Mars' gravitational field by noting where the spacecraft speeds up or slows down in its orbit. It will also help map the vertical structure of the Martian atmosphere. Each time the spacecraft goes behind the planet or emerges from behind it, the radio beams will have to pass through the Martian atmosphere on their way to Earth. From the way the waves are distorted by the Martian atmosphere, the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere can be determined. The radio relay system will relay data from future Mars missions and from future Surveyor landers.

The camera will provide a daily wide-angle image of the entire planet and narrow-angle images of objects down to 1.5m in diameter. It will provide views similar to those obtained by terrestrial weather satellites. Some of the pictures will be sharp enough to help selecting landing sites for future missions.

The JPL plans to follow up the Mars Global Surveyor mission with another orbiter in December 1998 and, in January 1999 it plans to launch the program's first robotic lander probe. Two more launches featuring another orbiter and a lander are planned for 2003.

The JPL plans to follow up the Mars Global Surveyor mission with another orbiter in December 1998 and, in January 1999 it plans to launch the program's first robotic lander probe. Two more launches featuring another orbiter and a lander are planned for 2003.

Concurrent with the Global Surveyor mission, NASA is conducting the Mars Pathfinder mission - the first mission under its Discovery Program. The Mars Pathfinder is scheduled to be launched aboard a McDonnell Douglas Delta 2 rocket a bit later than the Global Surveyor, in December this year, but reaching earlier, in July 1997.

It will enter the Martian atmosphere, and by means of a system consisting of a parachute, rocket braking system, and air bags, will place a lander and a four-wheeled minirover on the planet's surface.

The Pathfinder mission will be the first to land on Mars since the Viking missions of the 1970s, and will carry the first autonomous rover ever to explore the surface of another planet.

The Global Surveyor and the Pathfinder missions will operate independently from each other. The orbiting Surveyor will beam its data to Earth and the Pathfinder's lander will beam its information to Earth directly from Mars' surface.

The Pathfinder mission will be primarily an engineering demonstration of key technologies and concepts for future missions involving landers. It will carry scientific instruments to Mars' surface to investigate the structure of the Martian atmosphere, surface meteorology, surface geology, form, and structure, and the elemental composition of Martian rocks and soils.

The Pathfinder spacecraft will have a launch mass of 870kg. Its parachute will be deployed about 10km from the Mars' surface. Rockets inside the backshell will then be fired to further slow down the craft's descent. After a few seconds, the tether attaching the lander to the backshell will be severed and with the remaining fuel the rockets will carry the backshell and parachute away from the landing area. Finally, the lander will deploy the air bags for the final stage of descent.

Important engineering data will be obtained during Mars atmospheric entry by means of accelerometer measurements, air-stream pressure and temperature measurements after parachute deployment, and temperature data acquired from sensors inserted in the aeroshell.

A camera on the lander will use multiple colour filters to allow scientists to determine what minerals occur on Mars. Its pictures will provide a calibration point, or ground truth, to help calibrate future remote sensing information obtained from orbit.

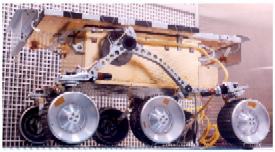

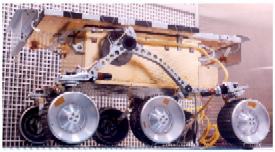

Once on the Martian surface, the rover will be operated initially for at least 7 Martian days (A Martian day is slightly longer than an Earth day, 24 hours and 39 minutes). If both the lander and the rover are still performing well after this period, the lander may continue to operate for up to one Martian year (about 687 Earth days), and the rover for up to 30 Martian days.

The rover, which will have a mobile mass of about 11.5kg, will be powered by a flat solar panel and a primary battery. Its six wheels are a rocker-bogle suspension system that permits it to crawl over small rocks. It will carry an instrument called the alpha proton x-ray spectrometer which will determine the composition of surface rocks. It will also carry aft and fore cameras and will communicate with the lander via a UHF link.

Concurrent with the Global Surveyor mission, NASA is conducting the Mars Pathfinder mission - the first mission under its Discovery Program. The Mars Pathfinder is scheduled to be launched aboard a McDonnell Douglas Delta 2 rocket a bit later than the Global Surveyor, in December this year, but reaching earlier, in July 1997.

It will enter the Martian atmosphere, and by means of a system consisting of a parachute, rocket braking system, and air bags, will place a lander and a four-wheeled minirover on the planet's surface.

The Pathfinder mission will be the first to land on Mars since the Viking missions of the 1970s, and will carry the first autonomous rover ever to explore the surface of another planet.

The Global Surveyor and the Pathfinder missions will operate independently from each other. The orbiting Surveyor will beam its data to Earth and the Pathfinder's lander will beam its information to Earth directly from Mars' surface.

The Pathfinder mission will be primarily an engineering demonstration of key technologies and concepts for future missions involving landers. It will carry scientific instruments to Mars' surface to investigate the structure of the Martian atmosphere, surface meteorology, surface geology, form, and structure, and the elemental composition of Martian rocks and soils.

The Pathfinder spacecraft will have a launch mass of 870kg. Its parachute will be deployed about 10km from the Mars' surface. Rockets inside the backshell will then be fired to further slow down the craft's descent. After a few seconds, the tether attaching the lander to the backshell will be severed and with the remaining fuel the rockets will carry the backshell and parachute away from the landing area. Finally, the lander will deploy the air bags for the final stage of descent.

Important engineering data will be obtained during Mars atmospheric entry by means of accelerometer measurements, air-stream pressure and temperature measurements after parachute deployment, and temperature data acquired from sensors inserted in the aeroshell.

A camera on the lander will use multiple colour filters to allow scientists to determine what minerals occur on Mars. Its pictures will provide a calibration point, or ground truth, to help calibrate future remote sensing information obtained from orbit.

Once on the Martian surface, the rover will be operated initially for at least 7 Martian days (A Martian day is slightly longer than an Earth day, 24 hours and 39 minutes). If both the lander and the rover are still performing well after this period, the lander may continue to operate for up to one Martian year (about 687 Earth days), and the rover for up to 30 Martian days.

The rover, which will have a mobile mass of about 11.5kg, will be powered by a flat solar panel and a primary battery. Its six wheels are a rocker-bogle suspension system that permits it to crawl over small rocks. It will carry an instrument called the alpha proton x-ray spectrometer which will determine the composition of surface rocks. It will also carry aft and fore cameras and will communicate with the lander via a UHF link.

The article above was taken from Engineering World magazine, February 1996 issue. Reporter: Paul Grad

Return To Space Menu.

Return To Space Menu.

Return To Space Menu.

Return To Space Menu.